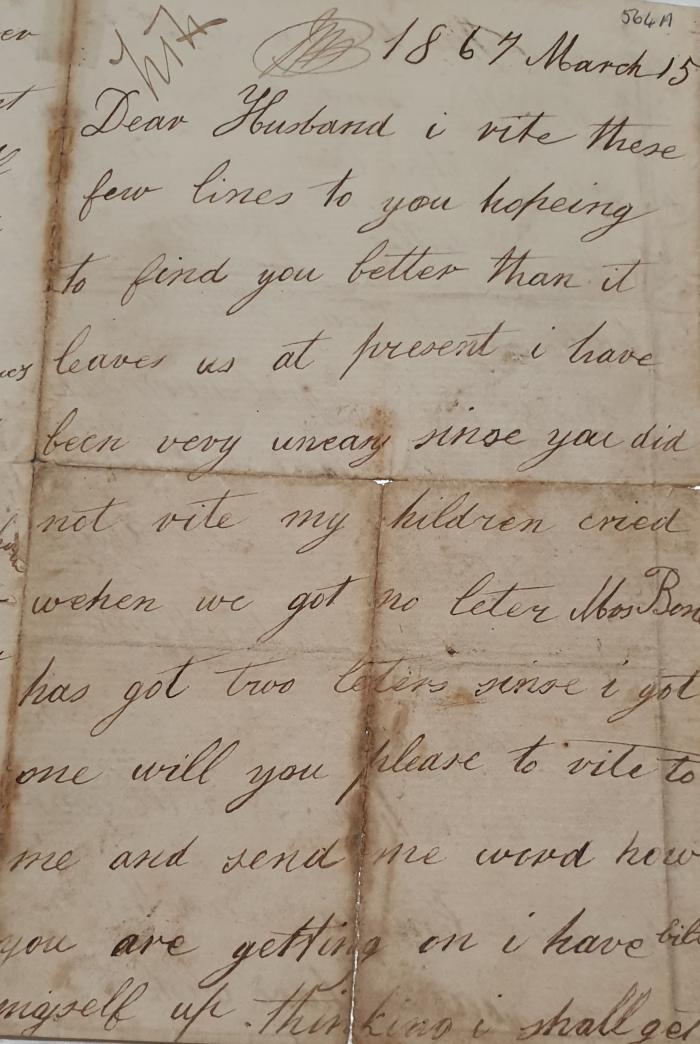

Join Dr Kate as she unearths the incredible story of the Toodyay Letters. A heartbreaking set of ten original letters written from the perspective of Myra Sykes to her husband, William, who was transported to the Swan River Colony as a convict in 1867. Myra lived in poverty in the Sheffield area, raising four children without her husband. She was largely illiterate. It was thought other people must have scribed the letters on her behalf. The letters range from the period 1867-1879.

William died in 1891 in Toodyay, and the family was never reunited. Dr Kate explains the survival of this set of letters is a story in itself and set the scene for preserving the convict history of WA.

These letters are not yet digitised but can be read in the books Alexandra Hasluck’s ‘Unwilling Emigrants: letters of a convict's wife’ and Graham Seal’s ‘These Few Line: the lost lives of Myra and William Sykes’.

Recorded on ABC Radio Perth on 3 December 2021.

Transcript

[Segment introduction. Male voice asking “What is history?”]

[Suspense instrumental music in the background]

[Different voices saying “Nothing will save the government... something revolving.... that’s one small step for... the world keeps revolving... just a little bit of history repeating, repeating, repeating....]

Hilary: Well, I wonder, have you got any old letters at home that have been handed down to you through family and generations passed, maybe some faded postcards as well. Letters really are a glimpse into what life was like for someone whether their bursting with love or heartache. They are a little window into another’s world and there’s a collection of ten letters written from a wife separated by 14,000 kilometres to her husband. They were written in the 1800s and known as the Toodyay Letters. Doctor Kate Gregory, Battye Historian at The State Library of WA is here to tell you more about the Toodyay Letters.

Welcome back to Afternoons Kate, great to talk to you.

Dr Gregory: You too Hilary, lovely to be here.

Hilary: Look, let’s start with the letters. Where were they discovered back in the 1930s?

Dr Gregory: Ah, this is just such a wonderful story in itself. Ok, so these letters were first unearthed in 1931. They were discovered when the Toodyay prison and jail complex which included the police station, the sort of law and complex order in Toodyay was being partially pulled down. So, they were discovered in a nook and cranny of a wall of one of the cells in this complex and they were handed to what was then The Historical Society of WA and later became The Royal WA Historical Society. So, somebody obviously recognised that they might be of value, and this is perhaps because they were found in a kangaroo skin pouch so just imagine it was...

Hilary: [astonishment] Wow.

Dr Gregory: ... the first side out and shaped apparently like an envelope and then these letters were, you know, carefully kind of stored inside. So, whoever had kept these letters had wanted them to be safe and had you know, very much valued them.

Hilary: And put them inside a wall.

Dr Gregory: Yes.

Hilary: The jail cell.

Dr Gregory: Well, that’s right. How they came to be there, we’re not entirely sure but they were given to The Historical Society in the 30s, but I guess the thing that is of interest... so research over the following years found out that they were convict related letters, so they were letters, as you’ve said, written by Myra Sykes to her husband who was a convict, William Sykes, and to that end they’re incredibly poignant stories and letters. You know, not only where they separated... you know, it was a terrible situation to be obviously transported to a penal colony, they were never reunited.

Hilary: [astonishment] Oh, wow!

Dr Gregory: This family was never reunited. They remained a very poignant kind of source of evidence, I suppose, of what this convict experience was like and at the time in the 1930s, the convict stain was very much a real thing. So, there was... and in particular this is why within The Historical Society at that time, there was heated debate about whether or not to even preserve these letters. Some argued that they should be burned.

Hilary: Wow. See that just is incredible to me. That it now in 2021... but... why was there that thinking at the time to destroy them?

Dr Gregory: Well, there were various kind of arguments mounted and one of which was “these are private”.

Hilary: Right.

Dr Gregory: These are private letters and you know, we shouldn’t’ make them kind of public, kind of thing, but I think that that actually, you know, behind that was the more pervasive kind of feeling that the convict history in Western Australia was a source of shame and in fact many of the people who were involved with The Historical Society were, of course you can imagine part of the old West Australian families, pioneering families who didn’t necessarily have convicts in their ancestry and there was a real feeling that this is something... kind of aberration; a part of WA’s history that was best forgotten.

Hilary: [astonishment] Mmmmm, wow.

Dr Gregory: [Laughs] Which today is you know, is just incredible to think because of the way in which now that convict ancestry has come to be recognised as something for many people a source of pride.

Hilary: Yep, and valuable and tells a story..

Dr Gregory: Valuable... yes.

Hilary: ... of you know, it’s the truth as well

Dr Gregory: Well, it’s the truth that’s right.

Hilary: Yes, so can you tell me more about what’s inside those letters and the content and what Myra is talking about in some of the letters to her husband.

Dr Gregory: Yes, absolutely and who they were I suppose as well.

Hilary: Mmmm.

Dr Gregory: So, I mean, I guess like many convicts, they were from an impoverished class within English society, you know, and they were from sort of industrial heartland of England as well living around in Yorkshire so William Sykes himself, he received no formal education. He was born in 1827 and he worked from a very early age in the coal industry, so you know, child labour etc.

Hilary: Mmmm.

Dr Gregory: Yes, and he met Myra and they married in 1853. They went on to have four children and at that time, he was working as a puddler which is something within the iron industry. I don’t know exactly what they do.

Hilary: Ah, let us know. Give us a call. 1300 222 720; a puddler P U D D L E R [spells out the word ‘puddler’]

Dr Gregory: That’s right.

Hilary: Something in the iron industry. Like an iron monger.

Dr Gregory: That’s right, yes well, that’s right, something to do with the formation of iron.

Hilary: Ok.

Dr Gregory: And I didn’t have time to look it up so...

Hilary: No.

Dr Gregory: [laughs] It would be really interesting.

Hilary: [laughs] Someone will know. Give us a call 1800 222 720.

Dr Gregory: [Laughs] So as you can imagine, I mean, you know means were very limited...

Hilary: Mmmmmm.

Dr Gregory: ... for this growing family and Sykes, as many as his contemporaries did often went poaching at night to you know, catch rabbits for dinner to feed the family.

Hilary: Wow.

Dr Gregory: ... and on this occasion in 1865 with six other men, they went poaching and they were challenged by a group of game keepers and a fight resulted and one of the game keepers was killed and so William Sykes and four of the others were actually charged with manslaughter and they received life sentences with a minimum of twenty years penal servitude.

Hilary: Wow.

Dr Gregory: Yes, this was when... the start of this journey to the Swan River colony.

Hilary: And so was there ever the intention... so he was obviously sent to serve out his term in Australia.

Dr Gregory: Yes

Hilary: Was there ever the intention that Myra and the four children would follow?

Dr Gregory: Well, interesting that you would say that because in the letters, Myra makes it very clear that she would like to be reunited. I did... I could actually read... there’s a lovely few lines that I might read to you if...

Hilary: Yes, that would be wonderful

Dr Gregory: And it gives you a sense... I mean Myra herself... so ok, she’s largely illiterate. She’s really struggling to write these letters. They’re written in four different hands, so we suspect that other people scribed them for her at some time.

Hilary: Right.

Dr Gregory: And we know that her son, when he was better schooled, he took on the writing on some of these letters. So, her punctuation is kind of non-existent, there’s lots of spelling mistakes, so it’s kind of written in a style which when you read these letters, I had a look at the originals yesterday and they’re just you know, to see the original letters is something else.

Hilary: Mmmmm.

Dr Gregory: It’s really fantastic. Unfortunately, the kangaroo skin pouch has been lost so we can only assume that that was at some point you know, kind of moth eaten and then discarded. We don’t have any record of when or what happened to that but though unfortunately that kind of...

Hilary: That’s gone but…

Dr Gregory: ... beautiful, evocative…

Hilary: Mmmmm.

Dr Gregory: ... peace of artefact has disappeared but this little passage, it gives you a sense of Myra, she says although we are separated, there is no one I value and regard equal to you and I should like you to still have the same feeling towards me and if there is ever a chance of our being permitted to join you again even though it be in a far off land, both the children and myself will most gladly do so.

Hilary: Wow.

Dr Gregory: So…

Hilary: [sadness in voice] It’s heartbreaking.

Dr Gregory: [sadness in voice] It’s heartbreaking.

Hilary: Yes.

Dr Gregory: They didn’t get... they weren’t able to reunite, so I think that look, in amongst these papers, there’s, so not only are there these letters that help to paint a picture I suppose of the toll of this experience you know on families, but also we’ve got in amongst the letters, what we’re calling a diary although it’s only really two pages very, very short account written by William in his hand of the voyage out to the Swan River colony on the convict ship, The Norwood. So, he writes this account, it’s a very brief, brief diary of the voyage and it’s extraordinary because of the fact that he was not schooled and was largely illiterate.

Hilary: Mmmmmm.

Dr Gregory: Um, but he does kind of describe, you know, so of the events on the ship, um, death and birth and sharks being caught, Albatross sightings. It’s really interesting and the wonderful thing is as well is, that alongside this in what we call a diary, although you know it’s kind of... it’s flimsy two pages.

Hilary: Yes.

Dr Gregory: Pencilled kind of really...

Hilary: ... journal.

Dr Gregory: Yes.

Hilary: Mmmm.

Dr Gregory: Um, we also have one of the ship’s newspapers that were written by hand called, The Norwood Yarna. We’ve got an original of this. It’s just incredible and this was a newsletter. This was kind of a practice that occurred on some of the convict ships and a lot of the convict ships where they would write a kind of weekly newsletter to everyone on board, that would report on ships happening and things to look forward to…

Hilary: Wow.

Dr Gregory: ... on that colony.

It’s amazing, it’s a really, really incredible record, so we’ve got that alongside... so you sort of start to see how these little fragments, you know, on their own they don’t seem much but when you put them together, you know, you start to build up this much more rich and kind of interesting view on what occurred in this convict path.

Hilary: Absolutely. You’re on ABC Radio Perth and WA with Hilary Smaile this afternoon and for History Repeated today talking to Dr Kate Gregory, Battye Historian, State Library of Western Australia about a collection of letters they’re called the “Toodyay letters” because they were found in Toodyay in the 1930s. They’re the letters from Myra and William Sykes, husband and wife who were separated after William was sent to Australia as a convict to serve out his term I guess as a convict.

Kate, why have these letters resurfaced recently?

Dr Gregory: Yes.

Hilary: What’s come up?

Dr Gregory: Well look, I mean the reason why I’ve kind of rediscovered these is because recently there was an addition of the journal studies in WA history which is called the ‘Castoral Colony’ and it won the recent Margaret Medcalf Award from the State Records Office. Just a week or two ago and so what this is, is that there’s, it kind of encapsulates a whole lot of really fresh thinking and new research around convictism in Western Australia and so I guess sparked off by that I started to think about what do we have in our collections that you know, tell this story, convict story.

Hilary: Yes

Dr Gregory: And then you know, came across these letters and they’re actually really significant for a couple of reasons. I mean not just for the fact that they’re evidence from a convict. They’re from the perspective of a convict kind of family, but also because they caused such contention in the 1930s with The Royal WA Historical Society and I think it’s just keeping in mind also that at that time, I think, the last WA convict is said to have died in like 1930 – 1931. So, at that time it’s still fresh, it’s still within living memory, you know so it’s kind of got a potency and a power that we are kind of bit...

Hilary: Removed from...

Dr Gregory: ... removed from, yes.

But also, I think then the role of Alexandra Hasluck, who in 1959 published this incredible book “Unwilling Immigrants” which is really based on these letters and she used William Sykes as what she called the prototype convict to kind of tell this much larger story about...

Hilary: Ahhh.

Dr Gregory: ...convict experience in Western Australia and at that time in the 50s I mean it’s only then and I mean even then it was kind of, it was really out there, it was a topic which was still much maligned so she was kind of venturing in to some sort of dangerous territory if you like but she published this book and it’s a wonderful book and then I suppose in the seventies through the work of Rika Erickson and others around the 150th anniversary, the sesquicentenary. There is a lot of work around recuperating the histories of everyday West Australians which included convicts you know and recognising that you know this past is significant and we need to preserve it, you know, I mean we know that convicts are responsible for building many roads, bridges, much of the colonial infrastructure buildings, many buildings that we you know have today and I mean Fremantle especially and Fremantle prison of course was built by convict labour, so you know, there’s a lot that is in our built fabric which you know, hypes back to that convict era and yes, so it’s just they tell such an interesting story, it’s a much larger story than just the story of convictism.

Hilary: Absolutely and I mean, how do you reflect on how our attitudes have changed? I mean you are now...so it’s a story and then you are talking about them on the radio [laughs].

Dr Gregory: [Laughs] I know

Hilary: And at one time, the equivalent of your profession wanted to burn them.

Dr Gregory: Well, that’s exactly right.

Hilary: Yes.

Dr Gregory: I know. It’s an extraordinary turn around. I think that, yes, look it’s a different era that we live in and I think as you’ve said, this is kind of truth. This is part of our past and it’s very important that those stories are you know, preserved for the future.

Hilary: Mmmm, yes. Can people access the letters at all in any way?

Dr Gregory: The letters, it’s interesting. I was quite surprised that the letters are not yet digitised, so ...[laughs]

Hilary: Oh wow!

Dr Gregory: They will be getting onto that.

Hilary: [Laughs] Yes.

Dr Gregory: Making sure that they are digitised pretty soon.

Hilary: Good work.

Dr Gregory: ...because they are, you know what, you can actually read them through. There’s a couple of one Alexandra Hasluck’s book “Unwilling Immigrants” and Alexandra was of course married to Sir Paul Hasluck and the two of them really, we have to thank Alexandra and Paul for the fact that these letters were preserved, so they were involved with The (Royal WA) Historical Society for the 30s and they really argued that they were important.

Hilary: Yes, wow.

Dr Gregory: But also there’s a gorgeous book by Graeme Seal called “These Few Lions”, the convict story, the lost lives of Myra and William Sykes and he goes into wonderful detail, reconstructing the kind of biographies if you like of both Myra and William and using these letters and he reproduces the letters in full in this book and this is only published a few years ago and I’m just trying to see where it was published. I think it might have been... oh... this was published by the ABC.

Hilary: [Laughs] Oh, there you go!

Dr Gregory: [Laughs] ABC books!

Hilary: [Laughs] Well done ABC Books. There you go!

Dr Gregory: So, it’s a lovely one.

Hilary: Yes. Can I just let you know that a puddler, this is Sarah’s wonderful work. It’s Sarah’s last day today, so we’re all a bit sad and a bit on a sugar high, but a puddler is a worker who turns pig iron into raw iron by puddling. Puddling is a step, in the manufacture of high grade iron, in a crucible or furnace.

Dr Gregory: Right.

Hilary: So, there you go. So that’s what William did.

Dr Gregory: Yes.

Hilary: Before coming to here to…

Dr Gregory: Yes, a pretty hard life and then obviously a very hard life here and he did get his ticket of leave and he lived the rest of his days around Toodyay. It was known as Newcastle then. He was building the railway in fact between Clackline and Newcastle, living alone with his dog in a railway hut, presumably with these letters, at that time I think which was in the 1880s, so when he thought he procured or made, we don’t know, the kangaroo skin pouch to keep these letters in.

Hilary: Did you say Toodyay used to be called Newcastle?

Dr Gregory: Yes, yes.

Hilary: [astonishment] I didn’t know that.

Dr Gregory: Yes, yes.

Hilary: [astonishment] There’s so much more [laughs].

Dr Gregory: Yes, it’s endless.

Hilary: And just before you go, a wonderful text from Kate here talking about old letters. Kate says, “I have a collection of letters written by my grandmother from boarding school, Ms Parnell’s during the first world war. I also have posted postcards from my great-uncle sent from Egypt. He lost his life at the Battle of Mouquet Farm in 1917. These are very precious to me.

Dr Gregory: Mmmmm, oh absolutely.

Hilary: So, they really do just shine a light on a different world, don’t they?

Dr Gregory: Mmmm.

Hilary: Yes. Kate, thanks very much for your work today and this year as well.

Dr Gregory: Well, it’s very amazing that this is the last interview for the year.

Hilary: Yes.

Dr Gregory: It has been a pleasure, thank you.

Hilary: We’ve learned so much and really looking forward to having you back in 2022.

Dr Gregory: Yes, I’m looking forward to it too.

Hilary: Enjoy your break.

Dr Gregory: Thank you.

Hilary: Doctor Kate Gregory there, Battye Historian at The State Library of Western Australia and talking there about the incredible Toodyay Letters of Myra and William Sykes. Wonderful to have you with me here on ABC Radio Perth.