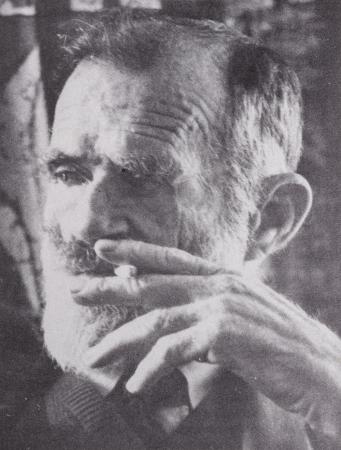

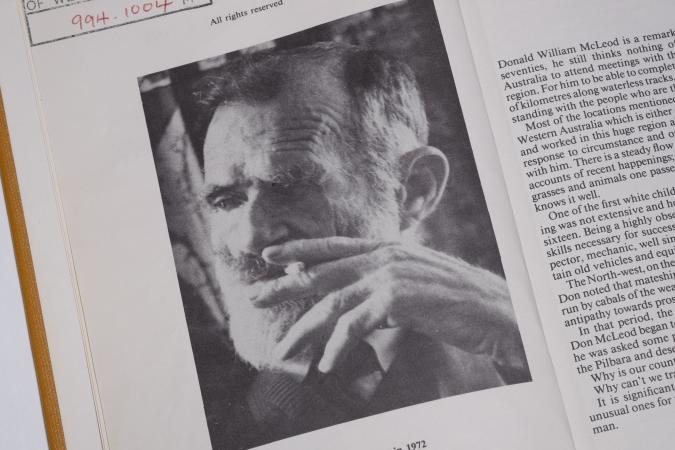

The State Library has many documentary highlights in its archive. One of the highlights is a collection of letters to and from one of the major activists for Aboriginal rights in the twentieth century Don McLeod. Don is most famous for being chosen by Marrgnu people of the Pilbara to be their spokesperson during the Pilbara Strike, which lasted three years from 1946 to 1949. Later he was also involved in the Noonkanbah land rights controversy in 1980.

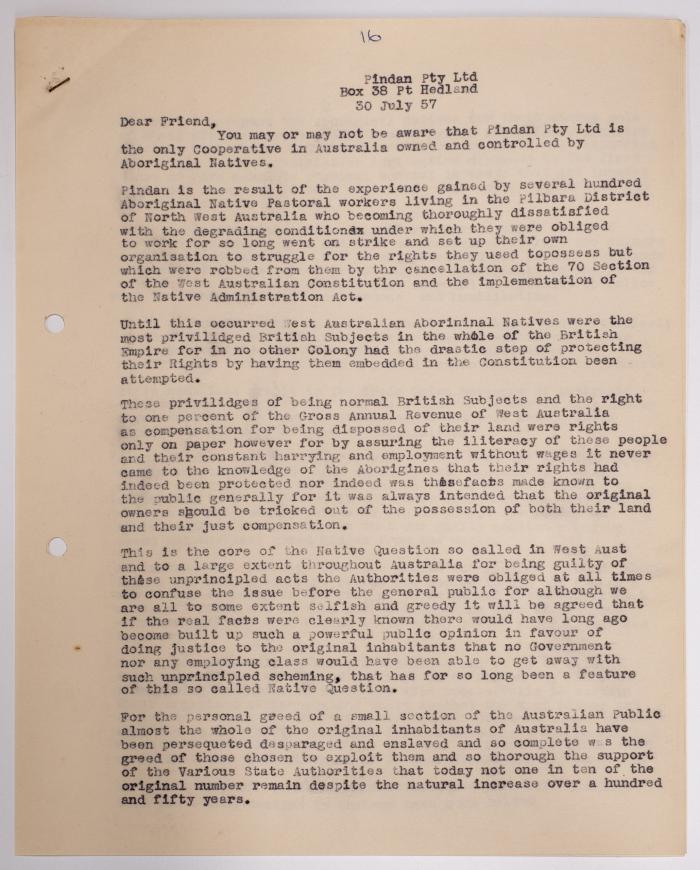

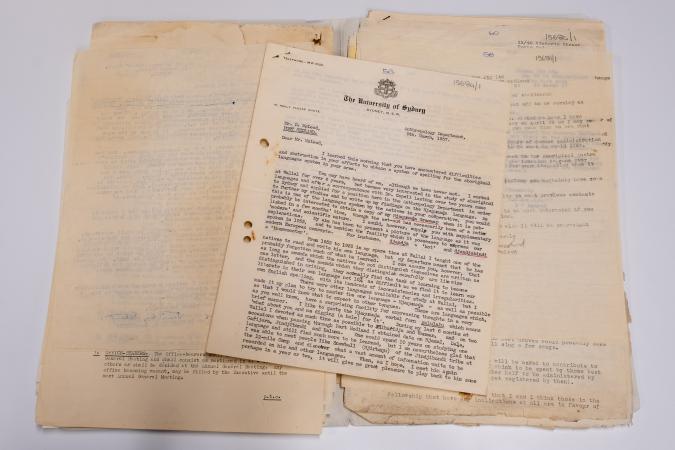

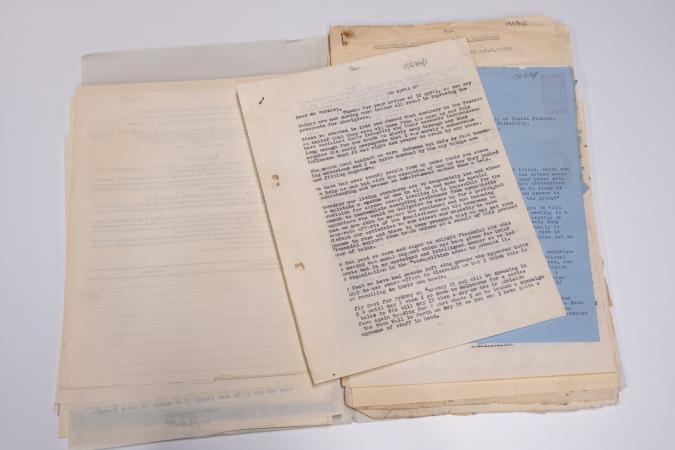

The letters at the State Library encompass a later period of Don’s life in the 1950s when he was a regular correspondent across Australia and the world advocating for Aboriginal human rights. In 1957 McLeod helped run the Aboriginal owned Pindan Cooperative in the Pilbara and spent a lot of time advocating for and managing their affairs.

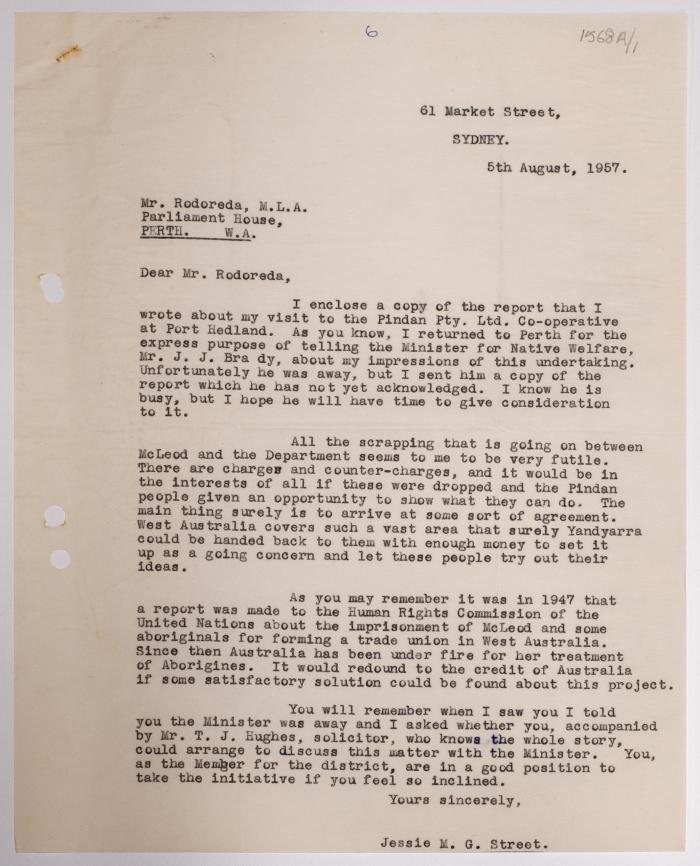

There is a stream of correspondence with Lady Street (Jesse Street), who was the only female in the Australian delegation to the inaugural United Nations meeting in 1945. Lady Street also campaigned for Aboriginal rights and visited the Pilbara.

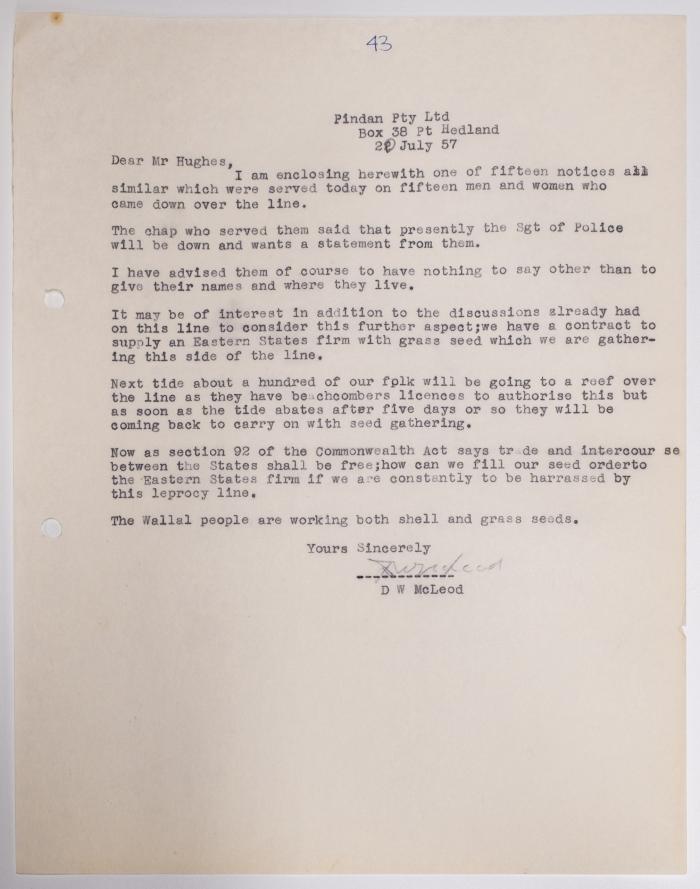

Another series of letters deal with the lack of free movement of Aboriginal people below the 20th parallel (Leprosy Line) that Don campaigned against.

Don McLeod died in 1999 and appropriately was buried in the Pilbara at Strelley Station.

Transcript

BEGINNING OF INTERVIEW

Christine: It became one of the longest strikes in Australian history. Prior to this many Aboriginal workers relied on rations of tea, coffee and sugar from station managers.

We are going to learn how this movement began and how it shaped the region to this day.

In the studios I have John Hughes, Senior Subject Specialist at the State Library of WA.

Hello John.

John Hughes: Hi Christine.

Christine: Now, before we get to the history topic of the day, you were stuck. Last night you used that particular train. What time did you get home last night?

JH: I actually went in the door about eight o’clock in Halls Head.

Christine: [Gasp]

JH: So, it was pretty hot waiting on the…waiting for buses at Cockburn yesterday afternoon as you can imagine [laughs].

Christine: Oh no. Eight o’clock, that’s so late. So how long did it take you to get home in total?

JH: It probably took well over two hours. Yes.

Christine: Yes, yes.

JH: It was a bit of a drag [laughs].

Christine: As you mentioned, we’re all getting used to a bit of hardship.

JH: Yes, yes well, it kind of segues nicely into the Pilbara in the 1930s and 40s.

Christine: Yes, so tell me, tell me about this topic. You’ve come to talk to us about Don McLeod. Now who was Don?

JH: Don McLeod - he was born in 1908 in Meekatharra up there. He was a working-class guy. He left school early. He wasn’t an Aboriginal person, but as he went through his working life, he was a prospector, miner and general handyman up there. He developed really good relationships with Aboriginal people up there and they came to trust him and so they trusted him so much that they asked him to be the intermediary when they went on strike…when they left the stations in 1946 and they asked Don to be the intermediary with the white authorities and to negotiate on their behalf. So, it was a pretty big burden that they put on his shoulders but he embraced it.

I think in…he was a really interesting character. He was a really tough guy. I think with the phrase we’d use nowadays is he probably didn’t suffer fools gladly [chuckles]. But he had to be incredibly tough because once he got involved with the Aboriginal, essentially a human rights struggle in the 1940s, that carried him on until the end of his life in 1999. So, he just carried on battling. So not only do we see him at the front in the Pilbara strike and imprisoned because of that, in the Noonkanbah drilling affair in 1980 he was also at the front there, so thirty years later he was still involved and still fighting for Aboriginal rights.

Christine: It takes a certain character and you know the fact that they trusted him is huge. Can you tell me more about the climate at the time? What was this situation like?

JH: It was really pretty desperate. Obviously, there’s been…recently there’s been a huge political debate about perceptions of slavery in Australia. A lot of literature you read about this do characterise the way that Aboriginal people living in the Kimberley at the time as slavery. A lot of people weren’t paid as you said in your introduction. They were paid rations.

One of the things that really influenced their lives was the 1905 Aborigines Act which meant they had to get permission before they could be married. They couldn’t move off stations without permission. As we know from the Stolen Generation, children were removed from Aboriginal families’ willy nilly. Aboriginal stockmen were housed in humpies often without floors, lighting or sanitation. So, it was a desperately hard way to live in a kind of an exploitative, paternalistic environment.

So, the relationships were complex, but I guess for me it’s summed up by…in…they had this big meeting in 1942 to say well what are we going to do about this situation. The Marrgnu people up there and people from wider afield. They said, “What are we going to do about this situation?” and the question they posed to Don was, “Why is this no longer our country and why can’t we move around without being arrested?” and to some degree that sums it up.

Christine: It’s a fair question definitely.

Quarter past two.

My guest is John Hughes, Senior Subject Specialist from the State Library.

We are talking about one of the longest strikes in Australian history. It happened in the Pilbara and Don McLeod is the man that we are talking about.

So, what do you have at the State Library in terms of the archive? What do you have from Don?

JH: So the archive is really interesting. We’ve got hundreds of Don’s letters from the 1950s so by this time the strike is over but we have to remember it was a pre-internet age. Telephones weren’t as readily available, certainly not mobile phones.

So, he was in permanent correspondence with numerous people, so primarily the Department for Native Affairs. So, what he was doing was, he was a clever man because what he was…he was running test cases so that Aboriginal people could get pensions and could get child support just like everybody else in the state but it was very hard because he was fighting a racist system so he was constantly writing to the Department of Native Affairs and obviously they became familiar with one another to a large degree because they’d be like, “Oh no, it’s that bloody Don McLeod again.” You can imagine, can’t you? And then he’s corresponding with Aboriginal leaders, human rights activists and on a more mundane level, farm suppliers because at this stage they were…that he was setting up with Aboriginal people, they were in companies, they were in businesses, they took over Strelley Station, they set up a company called Pindan (not to be confused with a more modern Pindan).

One of the more singular bits of correspondence is with somebody…Jessie Street…Lady Street. So, when I first started reading these letters, I was really intrigued. Who is Lady Street? So, she was a feminist and campaigner and she was one of Australia’s first delegates to the founding of the United Nations in 1945 which is absolutely fascinating. So, she went…well she came to WA, supported the struggle for human rights and actually wrote a report on the Pilbara.

Christine: Did she?

JH: And then the other fascinating thing I found out about her which some people will be aware of, is there’s still a Jessie Street National Women’s Library in Sydney. So, I’m like, “Go Jessie.” [laughs].

Christine: Oh, yes, where is she originally from?

JH: I think she was born in Sydney, I’m not too sure. I haven’t gone totally, totally into that part of it but reading the correspondence obviously it was like, “Dear Lady Street.” I was like “Who’s this?” [chuckles]

Christine: Yes, yes, who is this character and how is she helping. So, what happened with the strike at the time John?

JH: So, what happened, I think one of the real interesting things to talk about is the meeting at Skull Creek in 1942 where 200 Aboriginal people from all over the North came together and they met for some weeks and actually really had a kind of a serious meeting about what they could do and they picked Don as their intermediary as I’ve said and the authorities and the pastoralists because they didn’t understand Aboriginal people, because they didn’t respect Aboriginal culture, they didn’t think that they would have the wherewithal to strike or to do anything particular so they were kind of you know tapping their fingers sort of saying…

Christine: Underestimated them.

JH: Yes, and so May the 1st 1946, 800 men, woman and children walked off the stations and so there was a big shock…

Christine: Good on them.

JH: Where have these people gone? And so, there was tumult and it resulted in numerous people being jailed not least Don and the leaders of the strike who I should have mentioned earlier, Dooley Binbin and Clancy McKenna, hopefully we’ll go on to them a bit later as well. So they were all jailed and one of the big set pieces of the strike was 300 of the Marrgnu people walking down the main street in Port Hedland to demand that Don be released and that was pretty symbolic because what it showed was there’d been a real change in Aboriginal people’s relationship with the pastoralists in Aboriginal people’s relationship with the police because there was a spirit of civil disobedience and it was kind of well you can fill your jails, you can arrest us as many times as you like, but we are now going to exercise our natural rights to be free people in our own country and so that was one of the powerful results of the strike. It didn’t mean that everything was fixed of course, you know there are still issues today. But that was really one of the significant things. The strikers gathered in two places – Twelve Mile camp outside Port Hedland and a place called Moolyella, I hope I’m saying that right, outside Marble Bar and because of Don’s background in mining, they were able to mine for tin on the surface at the Moolyella camp and that kept them going, and it also gave them a business plan for…because they didn’t know the strike was going to end in 1949. You know hindsight is a really easy thing, isn’t it, well it was going to be this. So they had to do something to feed themselves, so they were mining…tin mining at Moolyella.

The other thing which I think is a little bit amusing is there were lots of supporters in Perth. Some of whom were communist party activists and supporters. And there was a guy called Graham Alcorn who edited the Workers’ Star because the media at the time wasn’t reporting on this strike. There was silence but Graham Alcorn and the readers of the Workers’ Star were getting told about it. Graham Alcorn lived in Claremont and his flat was nicknamed ‘The Kremlin’ so...

Christine: Why? Oh ok [giggles].

JH: [Laughs] So, I was pretty amused when I read that.

Christine: I’m with you. Yes, I’m with you now, yes. So what did Graham do? What do we know? What…did he report on it?

JH: Well, yes it’s quite interesting. There were a lot of people who were attracted to that side of politics at those time. Obviously one of our most famous writers is Katharine Susannah Prichard. You know the reading centre in Greenmount. Well she was a member of the Communist Party and talking about the Kremlin, she wasn’t just a card carrier and a discusser. She actually went to Moscow to congresses and things like that. So there’s pictures of our own dearly beloved Katharine Susannah Prichard in Moscow. Set piece pictures of her which were set up by the people over there. So there was a whole group of people who wanted to see change in society I guess and this was a vehicle for that to occur.

Christine: So you mentioned some names, you mention Clancy and Dooley. Yes, who are they?

JH: So Dooley Binbin, he was the guy who was chosen to lead the strike and Clancy was also one of the key people, so a very picturesque avocation of Dooley is at the beginning of the strike, obviously he didn’t have a car to drive around the Pilbara so Dooley used a bicycle and he cycled around the Pilbara before May in 1946 handing out calendars and saying to people, “This is the day you need to strike”

Christine: Really?

JH: Or you know, however you want to record it, “This is the day you need to do it.” So Dooley Binbin and Clancy, they were the steerers of the strike, the leaders and they kind of used Don to talk to the white authorities and to negotiate on their behalf.

Christine: Gee, so what happened in the end?

JH: Well, by about September 1949, there was a great deal of pressure on the pastoralists from the Western Australian government to settle and if you read the letters and the notes of the time, at least in writing, the Western Australian government is acknowledging the totally unacceptable conditions in which Aboriginal people are living in the Pilbara. So they put a lot of pressure on the pastoralists to settle. So by September 1949 what happened were there were a lot of individual contracts made between stations and workers and the Native Affairs Department facilitated that, but some people didn’t go back. Some people stayed in mining in Moolyella and they stayed…they stayed essentially with Don and as I mentioned they set up a company called Pindan. They took over Strelley Station and it was kind of…I would suggest the emancipation of Aboriginal people in that area which obviously is hugely exciting that they were able to take their own destinies in their own hands which is fantastic.

Christine: Yes, and there’s a film. So 60 Years On, a film that was made. It’s called How the West was Lost.

JH: Well two films. So, 60 Years On was a film made by the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre in 2006. I am less familiar with that film. The film which has become slightly iconic is How the West was Lost which was made by David Noakes in 1987 and that film was…it kind of circulates a little bit underground. At the State Library we’ve tried to make it a bit more overgrown so we have a streaming service called Kanopy. This is a shameless advertisement.

Christine: Yes, tell me. Yes.

JH: We have a streaming service called Kanopy which is available in all Western Australian public libraries, state library and you can run How the West was Lost on that streaming service.

So if you wanted to watch How the West was Lost this afternoon, use your library card, go on to Kanopy and watch How the West was Lost. And it is a great film because it interviews all the main protagonists and really takes you to the Pilbara to experience it.

Christine: Wow, and in 2010 I was reading that Australian singer Shane Howard wrote a song about the Pilbara strike.

JH: Yes, they…he…there were earlier songs based on a poem by Dorothy Hewitt who is a very famous West Australian poet but also a communist and her poem…it was written in 1946 and I was thinking about this, and I was thinking isn’t it sad that we don’t have poets who write about this sort of thing nowadays and then of course John Kinsella came into my mind who wrote a poem called Bulldozer about the Roe 8 protest. So we still have poets as social activists who are doing this sort of thing.

Christine: Yes, interesting. Well yes look I’ve got a little grab of the tunes so this is called Dooley, Clancy and Don McLeod. Have a listen:

[Music plays]

“Station after station

Dooley spread the word

By foot and bike he spread the strike

While Clancy battled on.

McLeod worked on the wharves

Savin’ wages he didn’t need,

To send supplies to the strikers,

Things like flour and sugar and tea

The sound of freedom

It was ringin’ in the wind

The sound of freedom,

In the way the people sing.”

Christine: So that’s Shane Howard. Look at that! This has been a brilliant history listen John. I mean look, agonising to hear but important to know about. Thank you so much for coming in.

JH: That’s great, thanks Christine.

Christine: And I hope you have a better trip home tonight [laughs]

JH: [Laughs]

Christine: Nervous giggle. That is John Hughes. He is a Senior Archivist…sorry Senior Subject Specialist from the State Library of WA, so as you heard, you can go and watch How the West was Lost. If you can access Kanopy, I’m sure you’ve got your library card handy.

Speaking of….

END OF INTERVIEW