Left Right Out exposes the challenging legacy of how LGBTQ stories have been represented by our State’s cultural institutions, the State Library of Western Australia, the Western Australian Museum, and the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Left out of the archives altogether, overlooked, undescribed, or actively silenced – LGBTQ history has not been well recorded, preserved, nor exhibited by the State’s cultural institutions in the past.

Today, our cultural institutions are grappling with the challenge of making this history visible in collections and exhibitions. Alec Coles, CEO of Western Australian Museum, comments on the role of WA Museum Boola Bardip and continuing consultation taking place with the wider LGBTQ community. Curators from the Art Gallery and State Library are actively addressing these gaps through collection development and public programs.

This podcast brings together interviews with prominent West Australian artists and curators, including Alan Muller and Jo Darbyshire, who discuss the importance of queer history being represented by our cultural institutions. Dax Jagoe, a young trans activist, reflects on what it means for young trans people to see their experiences represented.

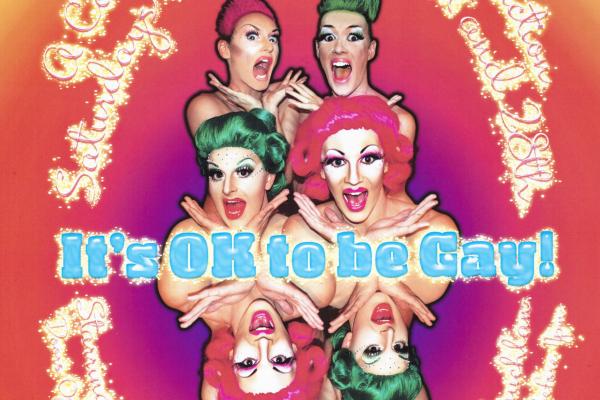

In the context of the 2017 referendum for same-sex marriage, this podcast explores a critical moment in the history of LGBTQ rights and the positive steps that cultural institutions are making.

Rare Stories from the West is a State Library of Western Australia podcast series. Through these podcasts, we hope to unearth tales of Western Australia’s past and present. Left Right Out: Queer Disclosure is the last of three podcasts produced by Gina Pickering. Part 1 - Walking on Water: Spirit of the Swan Coastal Plain, and Part 2 - On the Frontline: Rare Women of the West are available on SoundCloud and the State Library of Western Australia website.

Podcast created by Gina Pickering - Latitude Creative Services and commissioned by the State Library of Western Australia.

Transcript

Gina Pickering: Hi, this is Gina Pickering. I’ve been telling stories about Western Australia since the 1980s.

Over the last 20 years, these yarns have focused on the exceptional cultural aspects of the South West / Noongar Country. In this podcast series, I’ll explore three surprising stories through the voices of Aboriginal Elders, artists, curators and historians and how the State Library of Western Australia is responding to the cultural demands of change in our time.

Representation of the LGBTQI+ community in cultural institutions is hitting new highs and new hurdles.

A history of invisibility, conservatism and legislative reform has in many ways shaped queer lives in Australia in the most brutal ways.

[Music]

Revealing those stories publically exposes a challenging legacy of absence within our libraries, museums and galleries.

The State Library of Western Australia is investing in the LGBTQI+ community to capture its culture and its history, highlighting old tensions and fresh new responses along the way.

[Music]

Alan Muller: I remember putting a work in an open painting competition at the Fremantle Art Center in 1981. The work was called Wet Dream, and it was a painting of my male partner at the time, naked from neck to knee, pressed up against a wet sheet.

I was shocked that I won that award, because I was quite fearful of actually putting that work in that show.

And that was a real affirmation for me about the power of the arts to cross over those barriers of legislation, and actually say to the audience, we are here. This is who we are.

I'm Alan Muller. I'm a visual artist from Western Australia.

[Music]

Jo Darbyshire: So museums have a lot of rules and perhaps this is one of the reasons why artists are drawn to working in them, because questioning rules is one of our strengths.

Hi, I'm Jo Darbyshire. I'm a visual artist and a social history curator living in Fremantle, Western Australia.

And in the early 2000s, I was very interested in what artists were doing in museums and how they were working as curators in museums, particularly Joseph Kosuth at the Brooklyn Museum with The Play of the Unmentionable, which he was looking at censorship and also Narelle Jubelin an Australian artist at the Museum of Sydney.

And I realized that in the strategies that they were using from the visual arts were actually incredibly vibrant and could deal with problems that we had in the representation of lesbian and gay people in Australia, in museums, which was an absence of evidence. And the way that they dealt with it was to use metaphor. So I approached the Western Australia Museum as soon as we had gay law reform, which was in February, 2002 with the idea that they have me as an artist in residence and they hesitated. But they agreed as long as I did a master's degree.

Alan Muller: It was really interesting to me that the art gallery bought a work from 1985, called Making Up, which was about a famous drag queen in Perth called Natasha. His real name was Gary Donahue. And I think the fact that that work was collected now, but it was made decades ago, perhaps indicates that gap in cultural institutions collection. But I'm thrilled that they bought that work.

Sue Broomhall: A quality of rights should mean a quality of representation, and anything less is detrimental. So, where visitors come to cultural institutions and they don't see themselves in it, it's a problem.

I’m Professor Sue Broomhall, Historian with the Australian Catholic Museum.

Everybody has a right to be represented, to feel welcome, to feel comfortable, but also to see their stories visualized, and their histories told. Representation and diversity matter for people to be able to role model what it is to have an artistic life, or to contribute to public culture, and to achieve, and to see these being recognized as achievements, with identities that they share. So, it's a fundamental part of role modeling to be able to see people like yourself in cultural institutions.

Alan Muller: But it's more for young people looking at successful artists, knowing that they're gay is about knowing that they too can succeed, that they too can be a well known artist and be who they are. It's very interesting how families have destroyed artwork, destroyed letters, destroyed drawings of family members who were artists that died, because they did not want the public to know that they were gay.

Kate Gregory: I'd love to see more queer histories being represented in the State Library collections. And I'd also love to see more research into our collections to find out and recover the possible queer histories that we actually already have within our collection.

I’m Kate Gregory, Battye Historian with the State library of Western Australia.

Every now and again, we stumble across these materials and there could be letters, there could be photographs. And we just think there's another story here. If only we had more information, if only we could get to the bottom of these stories. We're quite sure that there are queer histories, but they are hidden. They're embedded in our collections. We'd love to see them brought into the light and we'd love to work with the contemporary community to help us to do that.

Jo Darbyshire: I think when I did The Gay Museum, I tried to embed homosexual history into the very walls of the museum. I made a conscious effort to use the walls, not to import panels, and I did this because I wanted the museum to own the history, not to just import it. And I wanted to make the point that homosexual people were always here.

In many ways I think the sector in WA, which is what I can really only speak about, has tried to be a little bit more inclusive of marginalized groups. And perhaps they have been open to collect LGBTQ materials and stories. But truthfully, I think that if there's not an actual lesbian or gay curator on staff, then access to our communities is limited and the curators are so seen to be very reticent to actively collect, or even to interpret this social history.

And I'll give you an example, in 2017 I collected the high vis clothing from a woman that I knew who worked very high up in the mining industry for Andrew Forrest. And I knew the WA Museum would be pretty interested in having items like this which represented women in mining. And I made sure that they knew that the donor was a lesbian, an art lesbian and in fact, she was happy to share this information. So although the museum did acquire the objects, I heard later that unfortunately they just didn't know how to include the term lesbian under their search terms. And it's only if you ask the curator himself that you'd find out this information.

Sue Broomhall: So, there's a question of how responsive a catalogue can be to new questions and new presentations that we might want to make through the materials collected. And, what that means is that they can often act to obstruct and impede discovery of objects, and stories, and collections, because we simply can't use the cataloging tools to find them. So, I think catalogs are perhaps an understudied aspect of some of the challenges in recovering voices and new interpretations in museums. And, that actually a fundamental place we need to start to think how that tool can work for us in developing new frameworks.

Alan Muller: The biggest challenge is about visibility. I think there's the idea that because we've got gay marriage now, then we should just shut up and get on with it.

Dax Jagoe: My name is Dax Jagoe. I’m 26, I use they /them pronouns I’m a agender and pansexual. I definitely consider myself to be a visible trans person. I make sure I am visibly trans to make it more ok for other people to be so in our society and see that everyday.

In these cultural institutions I haven’t experienced any sort of representation of what I consider my culture or my identity.

I understand I’m a very small aspect of the community that is becoming a more vocal part but it’s no fun to know your history is not out there and the history of people like you is not being recorded well.

Jo Darbyshire: These institutions are very powerful. So for them to leave us out, it hurts. We need to complain, we need to ask for more.

When young people go to these institutions, our cultural institutions, and they don't see themselves represented, they don't see any lesbians, they don't see any young trans people, they don't see any gay people, then I think there's an internalized homophobia.

They don't know their own history and that is what is so sad about leaving it out.

[Music]

Alec Coles: I suppose it goes back to the whole principle of how we developed the WA Museum Boola Bardip, which was through an extensive engagement process.

So certainly the LGBTQI+ community were involved at various stages along the way, either through individuals or indeed through groups like Gay Pride, for instance. And we had a principle that said, we wouldn't speak for people that can speak for themselves.

This is Alec Coles, CEO of the WA Museum.

I don't want to be trite about it, but if you try and drill down to every single section of the community, there are always going to be omissions. There was certainly no conscious decision to omit any community. I'm sure this is a discussion we will have and agree to have with representatives of that community. And there's every chance we'll include future stories, but I guess it's about how explicit one is about this.

Daxs Jagoe: If there was more trans representation in these cultural institutions it would definitely make a positive difference I think it would allow other people to learn about us without having to directly meet us.

It shouldn’t fall to the trans people themselves to be educating people about their cultural history, it should be recorded and maintained.

Sue Broomhall: One of the challenges for presentations in cultural institutions is which identities of an individual come to the fore? A fantastically well known artist might also be gay, is that part of the representation that should take place in the museum? Did that individual feel that their sexual lived experience informed their art in a way that should be part of the public presentation? Or did they see their public achievement in that cultural space independent of their lived experience of sexuality? And, that's the kind of decisions that cultural institutions have to make, ideally with the individual concerned, if they can.

[Music]

Gina Pickering: The Art Gallery of Western Australia had a public and recorded long table gathering, inviting representatives of the LGBTQI+ community to come along and discuss lived memory around issues including AIDS, the epidemic of the '80s, and making connections with COVID now.

Dunja Rmandic: This is Dunja Rmandic, Acting Curator of International Art at the Art Gallery of Western Australia.

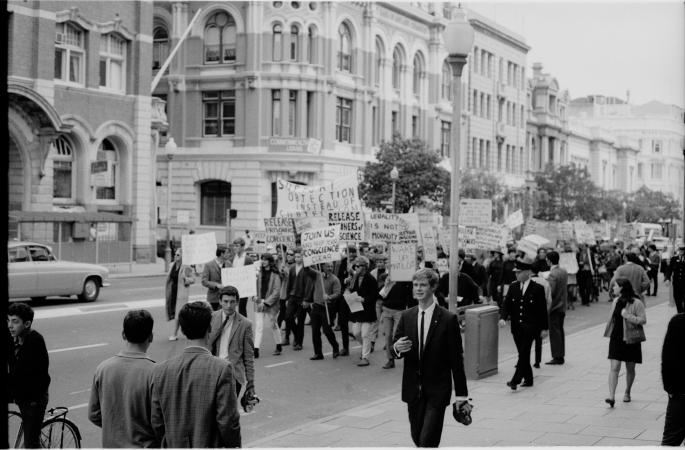

In 2019, I started conversations with Pride WA about commemorating the 30th anniversary of the March to Parliament.

And the first idea that I had was to display the work of nationally and internationally renowned artist, David McDiarmid's, and to think about how we do that within our collection displays and to tie in those conversations around those key issues, one with the institutional context but also within our collection and how to extend those stories further.

But another factor that was happening at the same time was COVID, and for me that was really important to think about because 30 years ago, we had another pandemic that the Queer community is very familiar with. And it was interesting that the stigma and the fear was replicated in the mainstream community around this global pandemic.

Dunja Rmandic:

I wanted to achieve with the long table was to invite people from the community to have a voice and to be very candid about their experiences, both as individuals and as a community and to contextualize all of these issues that I wanted to be brought out but also to do it from within an institution. So, to have them to enable them to have a platform, to talk about these things in an institutional context given that it is precisely the institutions which have been silencing the Queer community.

[Music]

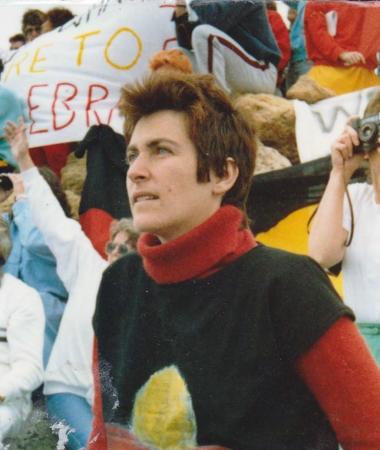

Gina Pickering: Participants came from every walk of life like Indigenous activist Esther Montgomery, Connections’ Tim Brown and Mark Reid from the AIDS Council and Brian Greig.

Brian Greig: I remember the Guild President at the time going into LT1 Lecture Theatre 1 to give a quick announcement that there would be a meeting to establish the Murdoch Uni Gay Society and within hours he was reprimanded by the Vice Chancellor for making that political speech and advised never to do that again because it would distress students. That was 84.

Esther Montgomery: In Aboriginal Australia we are oral historians, we don’t document. So what we need are people like myself and all the other elders who are alive to tell the stories, to tell the history and to document it because people have passed away, our brothers and sisters, and they were somebody and that’s why we need to tell the stories – each and every one of us – and carry it in the spoken word and document it.

Mark Reid: We understood to put a human face on the epidemic allowed people to understand what living with HIV was all about. And it was a tough lesson at times because people really had such naivety and ignorance about what it was to live with HIV. And in those early days we had to live with people dying all the time.

Tim Brown: You get given a family and they are your blood and you are related to them in all these different ways. But in the end, it is your blood that gives you your kinship there. Those of us who identify as different need to find a family somewhere else and that’s what we do. We’ve found this family ….

this is our family. This is our kinship group.

Alan Muller: I think the implications in the past have been brutal, because people grew up with huge issues to do with conflict within themselves, hating themselves. Being told that they were bad, being told that they were the work of the devil, are not the sort of messages which are going to give you a good life. So, it's been up to gay people to really claim their own ground, claim their own lives. A lot of people committed suicide. A lot of people ended up with severe mental illnesses, because the society just gave them terrible messages about who and what they were.

Dunja Rmandic: The kind of silencing that happens institutionally is really does come down to a decision, I think and that can be reversed in exactly the same way just by decision being made.

Jo Darbyshire: It's crucial that we have representations of queer community all through our cultural institutions, not only so that young people can recognize themselves and go, "Hey, that's talking to me," also so that they can learn their history.

Dunja Rmandic: We need to have queer curators, we need to have migrant curators, we need to have female curators with a lot more power because what that does is, that opens up networks for communication, collaboration, conversation, real meaningful structural networks, platforms that are genuinely open to common conversation, not on paper and not as a box ticked.

Sue Broomhall: There are some very exciting developments going on in the representation of LGBTQI+ communities in our museums. But, they are pushing back against an unspoken, often, assumption that heterosexual experience in life is the norm. And, what we have to do is open up and expose the ways in which that is fundamentally embedded in many of our cultural institutions in a number of ways. And, those ways range from the absolutely practical, about how objects are collected, how stories are told, whose voices are listened to, all the way through to how they come out on display. And, ideally, what we want is to push for curation and interpretation to be voiced and created by people who identify with the communities as much as possible.

[Music]

Kate Gregory: The State Library held a wonderful small exhibition a few years ago now called In Plain Sight. And it was really speculative. We were putting up these beautiful studio portraits and photographs of couples and groups of people in the past. We had a lot of really, really positive feedback about that exhibition. I mean, the images themselves are really beautiful and there's a lot more work to be done, I think, to recover these histories.

[Music]

Dunja Rmandic: The marriage equality debate time brought into extremely sharp focus, the fact that we did not have the same rights and we are not considered in the same way that other people are, that’s it.

Dunja Rmandic: There was a very tangible moment for me.

I was coming into work and // this feeling took over my body, it wasn't anxiety but it was just this, something between rage and anxiety, I guess. And I walked out onto a landing and I saw a colleague of mine who had just recently adopted a child with her husband and I thought, I am not as equal as you are. You and I are not the same. I come to the same workplace, I pay the same taxes, I do the same amount of work, if not more, and you and I are not equal. And that was a real moment for me when I realized that in fact, meritocracy doesn't work when it comes to these issues and being visible is a lot more important.

[Music]

Theresa Archer: In Plain Sight was an exhibition held by the State Library in 2017 and it was designed to do two things. One, highlight the absence of queer collections in the State Collections held at the State Library. And the other was to challenge people to think about the ways in which heteronormativity really influences the ways that we understand and think about history and the way that we interpret historical artifacts or photos or heritage sites.

[Music]

Theresa Archer: And so it was just a really slow curatorial process and definitely not the traditional approach to curating an exhibition.Once I got onto a set of studio portraits. Just going through them manually, one at a time, until I found photos that spoke to me.

This photo is one that I really like that was featured in the exhibition. Its two women. It's taken from around 1950, I think from memory, and they're in Northampton and they're holding two rabbits. I love their aesthetic, their dress, their overalls, the ammo strapped around one of their waists, and the way their hands are clasped together on this gun. It's just this weird merger of violence, but also closeness and intimacy.

We're starting to see an increase in the number of collections that are coming in that relate to queer and gender diverse people. There's beginnings of understandings within organizations about the special ways of these collections need to be managed and handled.

Jo Darbyshire: Nothing happens now without that Aboriginal first nation feedback and voice. And that is the level at which we should be asking and getting for our gay and lesbian history as well, because you cannot expect straight people to really understand. I mean, of course we have straight allies, of course, there's lots of heterosexual people who do understand oppression, and do understand a history of fighting in civil liberties. Right. But to actually talk about this particular issue, they should have advisory groups. They should have some people helping them.

Dunja Rmandic: Every generation likes to come in and say, well, we want to do things this way. But really what's harder to do but more important to do is to take that history with you, to know the history that came before you and incorporate it into your history, to slot your issues into that history so that you're not cutting loose that history.

You may also be interested in...