Join Dr Kate with Professor Jane Lydon, the Wesfarmers Chair in Australian History at UWA, discussing some of the oldest and most precious treasures held within the State Library collections – daguerreotypes, an early form of photography.

Jane’s research brings a new perspective to WA’s photographic history as part of the Collecting the West ARC Linkage research partnership with the State Library. She explores several examples, including a daguerreotype portrait of John Septimus Roe (1797-1878), naval officer, surveyor and explorer who in 1829 was appointed Surveyor-General of Western Australia.

Her research also reveals new information about a daguerreotype portrait of Mary Dixon, held within the Alfred Hawes Stone Album from the 1860s.

The State Library holds many special collections of early photographic forms, including ambrotypes, tintypes, opalotypes, panoramas, stereoscopic photographs and carte-de-visites.

Recorded live on ABC Radio Perth on 14 June 2022.

Transcript

Beginning of Interview

Christine: So you have heard the saying “A picture paints a thousand words”, but what does a photo do? I wonder what is the oldest photo you own and what is the story behind it?

Today on History Repeated, you and I are going to take a look at some of the earliest pictures taken in WA.

Joining us is Dr Kate Gregory, Battye Historian at the State Library of WA.

Hello, Kate.

Dr. Kate Gregory: Hi, Christine.

Christine: The smile in my voice. Always good to talk to you.

And we’ve got Professor Jane Lydon who is the Wesfarmers Chair in Australian History from UWA.

Hello, Jane.

Professor Jane Lydon: Hello, Christine. Very nice to be here.

Christine: Lovely to have you on.

Now, Kate, I’m going to start with you. Tell us about the photograph collection that you have at the State Library. Where does it start and what does it look like?

KG: Yes, well I think you and I have talked about the wonderful collections and particularly the photographic collections at the State Library on many occasions I think, Christine.

Christine: Yes.

KG: Yes, really kind of rich collection and it really spans the whole period of photography really from about the 1850s right up to contemporary photos and the aim of the collection I suppose is to document the Perth and West Australian landscape, people, events, places...it’s an incredibly rich collection and I think in the past, Christine, we’ve often talked about some of our wonderful twentieth century collections; the likes of Izzy Orloff and...so they kind of...a different style of photography but I think photographs really have the power of connection; the power to really make a connection. It’s kind of their direct ...and it kind of engaged the emotions I think and it gives you a really powerful kind of sense of people and places in the past. So they’re an incredibly rich source of information capable of transmitting a great deal of information very quickly in the image. So they’re a tremendous document and tool for researchers and I think also though, it’s apparent when looking at particularly some of our very early photographic collections how...what a different time and place Western Australia was in the 1850s and say the 1860s which is some of our earliest photographic collections. It is such a different place. Such a different culture and it’s hard to kind of connect with what was happening there, where is that landscape...trying to pin it with where we...with familiar places and buildings and people that we know of today.

Christine: Yeah, photos are so, so powerful aren’t they? And...

KG: Absolutely!

Christine: I had to learn how to say this, Kate, but I really want to learn more about daguerreotypes and Jane perhaps you can speak to this. What style of photography is in this collection?

PJL: [Laughs] Well, so you said that very well. Daguerreotypes are the very earliest kind of photograph and the State Library actually does hold several really very significant examples of this early sort of photo.

Christine: Daguerreotypes; so you have seen the collection. How big are they?

KG: Well the daguerreotypes are...generally daguerreotypes are very small and I think Jane will talk about this a little bit more. So some of the earliest collections are more like...and I think Jane describes this beautifully; it’s that they are more akin to kind of mirrors than what we think of images today. So you’ve got to angle them to the light. Generally able to be held in your hand and angled to the light so that you kind of catch the refle—almost like the reflection of the image. They are really...they are incredibly beautiful objects in their own right and I mean Jane can describe a little bit more about the process and everything but...

Christine: And we have her back which is good [laughs]. Welcome back Professor, are you there?

PJL: Yes, I don’t know what happened. I think Kate you’ve just put it beautifully. They call it the mirror with a memory [laughs] so ...

KG: That’s gorgeous. Yeah.

Christine: What do you mean by that?

PJL: Well, so when you looked at this very shiny plate, you basically saw a reflection but for the first time they were able to fix that image. So it was...this almost magical appearance where for the first time you could see an image or a person or a landscape from the other side of the world and this is something that colonists in Perth in Swan River really valued as well. They could record their prosperity where they were living, their family and send that in the mail back to their relatives back home in Britain as evidence to really show them what was happening.

Christine: So how long did you have to stay still in order to capture a daguerreotype Jane?

PJL: It varied a bit, depending on light and the conditions but from say a minute or two up to 15 minutes so as you can imagine [laughs] it would have been very...

Christine: Wow.

PJL Yes, so in some of them I actually love the ones where you can see that the baby’s been a bit wriggly or the pet has moved and they’re a little bit blurry. You can get a sense of what that would have been like.

Christine: So what does the photo of John Septimus Roe tell us?

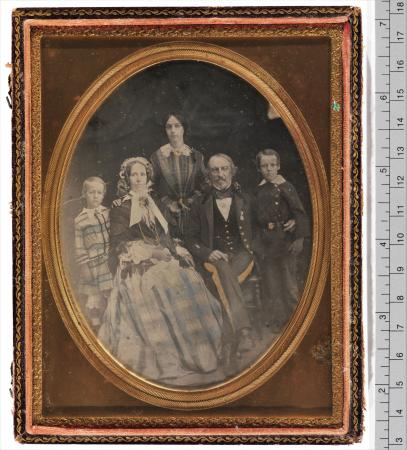

PJL: Well that is a real treasure in the Battye and it shows us a family who were among the earliest settlers who arrived in Swan River in 1829. So what we see is a very proud father and mother, husband and wife, John Septimus Roe and his wife Matilda and what we think are their three youngest children and of course they’re all dressed up, very much in the 1850s style but we see the family looking at the camera, except John is looking off to one side and once we learnt…yeah...and it fits in very much with what we know about his career; so he was born to quite a large family. So his middle name ‘Septimus’ means he was the seventh child and we know that as a kid he wanted to grow up and be a teacher but the family couldn’t afford it. He was born to...he was the son of the Reverend James Roe, Rector of Newbury and his family couldn’t afford to educate him. So when he was 16 he joined the navy as a midshipman and had many adventures in the Napoleonic wars. They found out he was very good at maths and drawing so he joined the surveying service and that was when he was...they first sent him to New South Wales but he was actually surveying the West coast and he had a terrible accident. He fell 15 metres and sustained a terrible wound above his right eye and in later years he lost the sight in that eye. So when we look at photographs, they are all staring straight back at the camera but he is looking off to one side and you can almost make out this kind of little indentation on his forehead which again is probably from that terrible accident.

Christine: That makes sense.

And look, there is a story of Mary Dixon as well and I really want to hear about this one, Jane. Can you expand? What does the photo look like and what exactly happened?

PJL: Oh well, we have a really interesting again these wonderful albums taken by Alfred Hawes Stone and they date probably to the eighteen sixties and eighteen seventies and Mary Dixon is sitting in her parlour in her very long, flowing dress of the style of the late eighteen fifties, eighteen sixty and she is looking very seriously off to one side and she’s holding on the table next to her a small daguerreotype of her father and...

Christine: Oh so it’s like an inception. It’s kind of...there’s a daguerreotype within a daguerreotype, is that right? [Giggles]

PJL: Exactly, exactly. So we have a photograph of Mary and then this little photograph and then a few pages on in the album, the photographer, Stone, has clearly taken a photograph of the daguerreotype and then pasted that into the album separately so we have that in its own right in the album, but what’s interesting is that the Dixon family came to Western Australia because her father was put in charge of convicts and...but then unfortunately was disgraced and what happened was he was paid into an account that was shared with his official, sort of expenses and he kind of mixed them up so...

Christine: Mixed them up deliberately or accidentally? [Laughs]

PJL: Well, it was a bit complicated. I mean people...historians are quite sympathetic but he definitely did the wrong thing and...so he was suspended and then he ran away to Singapore and then had various other adventures. He was actually a mercenary in the Taiping Rebellion in China and so on and so on, so it’s actually a very exciting life. But looking at this photograph, we see Mary and her father, and her father’s off having adventures around the world rather than being there or even being safely passed away so it’s...my colleague who has been researching with me, Martyn Jolly, said this is a bit like Christopher Skase you know…escaping justice...[Giggles]

Christine: And didn’t he go to Singapore because of the embezzlement and then he returned and lived with his daughter, is that right?

PJL: Yes, absolutely. So much, much later in life, so decades later he came back and he lived with Mary and her husband and actually died himself in Western Australia.

Christine: Yeah, wow that’s...I mean look the fact that you’ve got the photo behind the story I think is remarkable. Now what role do the Duryea brothers play in the collection? Is that how you say it?

PJL: Yes, very well done. It’s quite...I think that’s how they say it. So I’m doing this work with my colleagues, Elisa DeCourcy and Martyn Jolly, both based at The Australian National University and the three of us have been researching this very early history of photography and what Elisa has found is that the more collections we look in...so we started looking in collections like the Battye, The Royal Western Australian Historical Society and...but almost wherever we look we’re finding more photographs from this short period between 1857 and 1859 where we know that these two American born professional photographers were living and working and travelling in Western Australia so Townsend Duryea and his brother, Sanford, had come to Australia, they worked in Melbourne in the early 1850s, they worked in Adelaide in the middle 1850s and then they finally came over to Western Australia and so we’ve done this work that shows that they were advertising in York and Toodyay and they were saying,

“We’ll be there, we’ll be in Toodyay, we’ll be in Guildford on these dates...come and get your family photographed”.

And what’s exciting is that national histories of photography in Australia tend to be a little bit Sydney centric or...

Christine: Yes.

PJL: They certainly [laughs]...they don’t...[laughs] not a surprise but they tend to leave out the Western Australian history and they said, “Oh well not very much happened here”, but of course this research is showing that there was a tremendous amount happening and the Duryeas in particular seemed to have produced many, many of these family portraits and one of the interesting things that Elisa noticed is that a lot of the contemporary daguerreotypes that were being made in other places say in Sydney were very small. They were made on a quarter plate or a sixth plate in the camera so they were very small. They were relatively cheap and of course you could mail them. You could send them off to your family on the other side of the world but what we’re finding about the Western Australian ones is that they were often half plates or even full plates which means that they’re quite lavish. You know people are paying a lot of money and rather than putting them in the mail, they probably were keeping them on the mantelpiece or displaying them on a table. So, very much a sign of ‘we have made it, we have been successors here in the colonies’ and very much a sort of status symbol that they would have been proud of.

Christine: Yes, and I suppose maybe we’ve always been a rich state but when did it become affordable this style of photography? Was it around the 1860s? What happened after that?

PJL: Yeah, so daguerreotypes were relatively expensive because you needed to have a lot of know-how; technological know-how behind you. But then in the 1860s, they started to develop newer forms so what they called wet plate photography where you only had to pose for a few seconds and that meant that photographers could become more mobile, they could take photographs out of doors and then the dry plate was invented but the real breakthrough that democratised photography was the carte-de-visite, so this is where you took multiple photographs on a single plate, so all at once single exposure. You might have had 16 different images but it was much, much cheaper. So these are called ‘carte-de-visites’ which of course means ‘visiting card’ and they were just these small palm sized photographs and you could again just give them away, send them off to...put them in the family album. They were a lot more accessible. So that’s really when photography started to become that very, you know, everyday sort of...

Christine: Accessible.

PJL: Image that we know.

Christine: Yes.

Phil in Quindalup has sent me a text and it says,

“My great-great grandfather was a photographer in Belfast. I have a daguerreotype of him and his wife circa 1880 on their honeymoon. Apparently it was cool to send these to relatives in those days which speaks to everything we’ve mentioned”.

We’ve got news coming up so we unfortunately have to say goodbye soon but Dr Kate Gregory, how important are daguerreotypes to our collection hearing all of that?

KG: Yes, well I think, they are incredibly rare and special. They are treasures. They are treasures of the State Library collections. But I think also the other thing that I’d just like to mention quickly is that it’s only when researchers like Jane and Martyn and Elisa really apply their lens and you know all of their research skills to these collections that we can really understand their significance because they are from a very different time and place so it’s all of that contextualisation around for instance you know the story of Roe and his loss of eyesight and you know, the kind of wider context that situates these sources of evidence, these artefacts of the past and then that helps us to understand...much better understand their significance so that ...it’s hugely important and very exciting research. I think the other thing to say is that it’s part of the collecting the West ARC Linkage related to that as well which is looking at our West Australian collections in a very exciting new way.

Christine: I think it’s sad that he turned away from the camera just for the record. I mean that’s a comment on the times, isn’t it? He was perhaps ashamed or maybe somebody said something about it but it’s nothing to be ashamed of so yes, it’s really good to have you both on. Great to know the collection exists at the Battye Library. By the way Kate, is it publically accessible?

KG: Well they’re digitised so yes, the State Library is working very hard to conserve and preserve and digitise these very early rare collections so people can actually view them through the State Library website on our catalogue so you can just search for the very hard to spell ‘daguerreotype’ [laughs] or...or ‘Roe’. But I’ll tell you what, I’ll put some up on the website under WA Stories where the radio interviews are kept so that people can kind of have a look and see for themselves but yes, they are just really, really beautiful objects in their own right.

Christine: Definitely, look it’s been great to speak to you both.

Professor Jane Lydon thank you for coming on.

PJL: Oh thank you, it’s been lovely.

End of Interview