This week Dr. Kate discusses Raymond Stanley Stewart’s diary written on toilet paper while he was a prisoner of war in WWII.

The diary covers the period of 27 July 1942 to 12 September 1942 and details the day-to-day life as a POW in the desert camps of North Africa to the camps in Italy.

Who was Raymond Stanley Stewart?

Born in Northam in 1914, Lieutenant Raymond (Ray) Stanley Stewart of the 2/28th Australian Infantry Battalion enlisted in Northam in 1940.

Captured on 27 July 1942 at Ruin Ridge, El Alamein, Egypt, Ray was held as a prisoner of war in Europe from 27 July 1942 to 1 May 1945. He kept a number of diaries during this time. On 1 May 1945 he was liberated by American troops.

Ray returned to Western Australia via England and the Panama Canal and arrived back in Northam on train.

A year after returning to WA, he met Ivy Jeffrey, a widow with three sons under 3. They married in September 1947 and had two children. The family of seven settled in Coode St, Como and Ray worked as an engineer with the WA Government Railways.

Ray went on to become treasurer of the Como branch of the RSL and often attended meetings with long-time mate Bill Carlton, who was another member of the 2/28th Battalion. As well as being imprisoned together, they later became neighbours and worked together in the railways department.

State Library’s acquisition of the diary

The Ray Stewart collection was donated to the State Library in 1999. The State Library showcased the toilet roll diary as part of the National Treasures from Australia’s Great Libraries exhibition in 2005, after which, some medals and other documents were donated by his children.

The Ray Stewart collection includes not just the diaries and Red Cross gift box they were hidden in while he was a POW, but also theatre programs, menus, pay books, log books, and some correspondence.

About the toilet paper diary

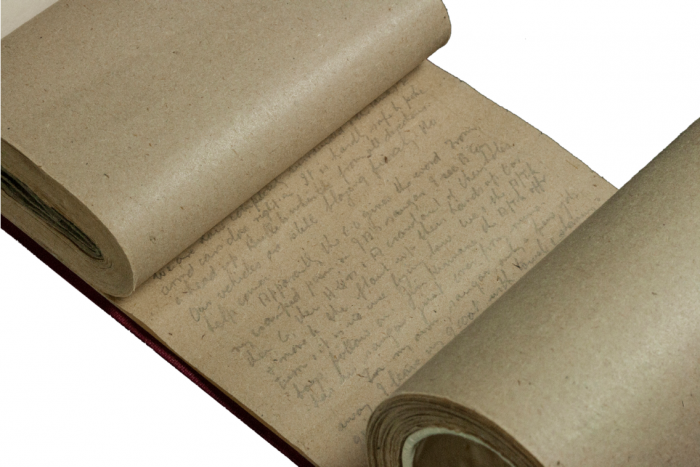

Keeping a diary was against camp rules, so in keeping it, Ray was taking a considerable risk. The diary is written in pencil on toilet paper, which is very fragile now – obviously something that was not designed to last!

The diary is stored in the Library’s rare materials stack in controlled environmental conditions to help preserve this very fragile item.

The Library digitised the diaries in 2016 and they can be read online, this further protects the diaries as their content can be accessed, but the physical materials do not need to be handled.

The digitisation process was challenging, given the nature of the object. The photographers in the Reformatting team said that it was the most challenging item they had ever digitised. The toilet roll diary took over twenty hours to digitise.

What does the diary say?

The diary provides insight into camp routine and the daily life of a prisoner during WWII.

[recounting capture] I feel miserable, angry, disillusioned and relieved in turn. I think everyone feels much the same way. The boys crack jokes to hide their feelings. Officers are deliberately destroying compasses and binoculars as the trudge along. Now the reaction is setting in. Everyone looks incredibly weary and every, very dirty. Many limp and swear. (p. 4)

[during transport to POW camp] We complain about our watches, food, water and medical treatment. They are quite affable and promise things, but nothing happens. Just at dusk we get some water and about six blankets. There must be thirty of us all told, and the blankets don’t go far. I share one with four others and we just stretch out on the bare ground. It’s cold and damned hard. The RAF comes over and bombs Matruh during the night. The bombs are landing on the foreshore just a few hundred feet away. Some of the shrapnel whistles horribly close. (p. 5)

Much of the content relates to food, transport, sleeping conditions, the treatment of POWs, money and commissary facilities, camp amenities, personal hygiene.

[Referring to Red Cross parcels – while in quarantine camp in Bari] They themselves open our parcels and open each tin. This is to stop anyone saving a stock of tinned food and making a break. In addition, they give us hot water to make tea. Each parcel contains a small packet of tea, two small tins of sugar, and a tin of milk… a tin of M and V (meat and vegetables), a tin of tomatoes, a tin of bacon, a tin of biscuits, a tin of pudding, a tin of butter, a tin of jam, a tin of meat roll, a tin of fish paste, a tin of cheese, a cake of soap, and a bar of chocolate. [he later notes that opening the tins also limits how much they can save and spread out the food, which was an issue because of its intermittent availability] (p. 10)

Our canteen arrived tonight. From it I got an exercise book (3 lira), a roll of toilet paper (3 lira), a tin of boot polish (2 lira) and 20 cigs (1 lira). Now I have no money left, but badly need some toothpaste which costs 5 lira. God knows when we will get any more pay. (p. 11)

Later entries in the notebook diaries, recount updates of the war, as Ray received it.

Today one of the S.A (South African) padres distributed Vatican broadcast message forms. The limit it 25 words each, but it is enough and we pray that the messages will get away soon so our people will know we are safe. War news is very scarce. A little filters through from the men via the medical staff, but it can’t be verified. We have no idea how the war goes. (p. 8)

Ray was careful not to include information that would help the enemy or harm fellow POW. For example, he didn’t document anything about their ‘special band practice’ – listening to BBC news broadcasts through a wireless receiver built into a piano accordion. If guards approached, they would quickly resume playing their instruments.

Other information omitted from the diaries include people’s escape plans, some which involved tunnelling and hiding dirt in cupboards until it could be unobtrusively spread about the yard.

Why is the diary significant?

In terms of SLWA holdings, Ray’s diaries are significant, not only for the physical format of the toilet paper diary, but also for the content revealing life in European POW camps. Notable, as these personal accounts focus on the day-to-day living, which is often absent from official war records and histories.

The additional materials in the Stewart collection further contextualise the content of the diaries and provide a fuller idea of life in the POW camps.

All of Ray’s diaries were transcribed by his daughter. The transcripts are available online through the State Library catalogue. They can be viewed for FREE by anyone, anywhere, anytime.

For more stories about the State Library's collections and materials, follow @statelibrarywa on Facebook and Twitter.

Recorded live on ABC Radio Perth on 14 April 2020.