As the first Western Australian State archivist and first female State archivist in Australia, Mollie Frances Lukis (1911-2009) played a major role in the development of the State Archives. With great vision and knowledge she built up the collection and agitated for change.

The below story is based on an oral history with Mollie Lukis interviewed by Erica Harvey in 1992 and contains images from different photo series from the State Library's collection. Mollie's words have been paraphrased for better readability.

The humble beginnings of our first State Archivist

I'm known as Mollie Lukis. My full name is Meroula Frances Fellowes Lukis. I was born at Donnybrook in the South West, in 1911. We lived at Balingup which is 25 miles further south.

There was no doctor in Balingup. My mother, who was 42 when I was born, wasn't really expected to have another child. My youngest brother was eight and the rest of the family were considerably older. My sister was eighteen when I was born.

My mother went to Donnybrook where they had a doctor. There was also a midwife there with whom she was supposed to stay but she found the place was so dirty she couldn't bear it. The doctor suggested to move into the hotel. So I was actually born in the Railway Hotel in Donnybrook.

My eldest brother went away in 1914 to the war, my second brother went in 1916.

I do vaguely remember when he left because we had a dairy and I was told I'd have to learn to milk. They got a very small stool and a small bucket and I did learn to milk to help take his place. I milked all the time while we were at Balingup, morning and night, which was an awful burden for a child.

Whenever I grumbled about anything I can remember my mother saying, “You must think of the poor boys in the trenches.” I got very sick of hearing about the boys in the trenches.

But the thing that does stand out was when my mother was accidentally informed that my eldest brother, who was in the Australian Flying Corps, had been shot down over in Egypt and killed.

I can remember very vividly – I had been with her to the post office – how we opened the letter on the way home. So that was a devastating thing until we actually heard that it was wrong.

There was another letter from a friend in the mail which they hadn't opened. It was from a nurse over there. She talked about my brother's plane being taken up by someone else and shot down and how fortunate it was he wasn't in it.

My brothers were complete strangers to me. It was a very lonely life for me because I was like an only child. The brother who was eight years older was away at school. I milked. I had a pony. The pony and the cows and my cat, were all pets to me. I used to have long conversations with the cows and the pony [laughs].

I didn't go to school in the ordinary sense. We were fortunate there was another family farming out of Balingup. Miss Connie Major had been in the Education Department. She had been well-educated before they came out here. She was able to teach me French.

My mother arranged for me to have two hours three days a week which is what I started with. But I think that someone reported to the Education Department that I wasn't attending school.

An inspector came to see how I was getting on. However, he found that I was getting on very well with six hours a week. Well with undivided attention of course, it does make a difference.

But mainly I was a lonely child. I was a tremendous reader. My father was always a very keen reader, but my mother believed that you shouldn't read in the daytime, and that you shouldn't waste your time. I suppose in a consequence of that I used to read secretly in bed under the bedclothes and sometimes I think in the morning when I wasn't supposed to be doing so.

I read everything that was in the house. We had a complete set which I suppose had belonged to my mother, of the novels of Walter Scott. I read them all, I think by the time I was ten. I learned very quickly how to skip what was dull and it stood me in good stead when I was studying in later years.

I read all the classics that we had, Scott and Dickens. There were a lot of my brother's books. I read Coral Island, all Ballantyne's books, that sort of thing.

I read everything that was available to read, and then of course I had suitable girls' books I suppose of the time: L M Montgomery and The Wide, Wide World which I can remember my mother reading to me before I could read. I lay in bed weeping while she read me this sad story.

My father used to keep an eye out sometimes. I can remember there was a book called The Sheikh, and he found me reading that and that was removed very rapidly. I think it was probably pretty harmless [laughs].

For my leaving year, I went to school at St Mary's in West Perth. I did enjoy those years at St Mary’s and I made some very good friends who are still my friends to this day. I was very shy at first.

Things were still financially difficult. We were all affected by the Depression. However, I think my mother particularly felt that if I wanted to have an academic education I should. By that time we had sold the farm. You see there were no fees for the university in those days. It was fairly reasonable, I mean, apart from the actual living and fares and things like that.

I studied at the Crawley Campus and I majored in English, French and maths. During university, I was teaching at a small school in Mount Lawley.

The gallery below includes photos of Mollie Lukis as well as some photos representing the time and places of her childhood.

The achievements of our first State Archivist

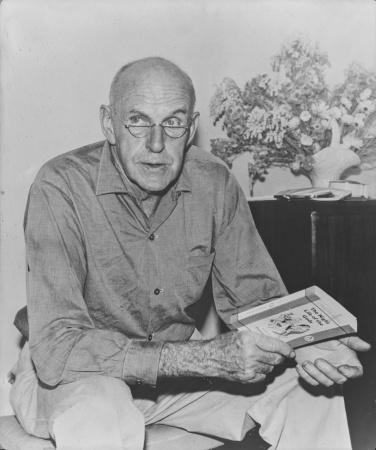

I had reached the stage when I felt I didn't want to continue teaching for the rest of my career. I saw the advertisement for this job in the archives, because I was reading the job advertisements all the time, just wondering what might turn up. I didn't really know what it would involve or what it would be [laughs].

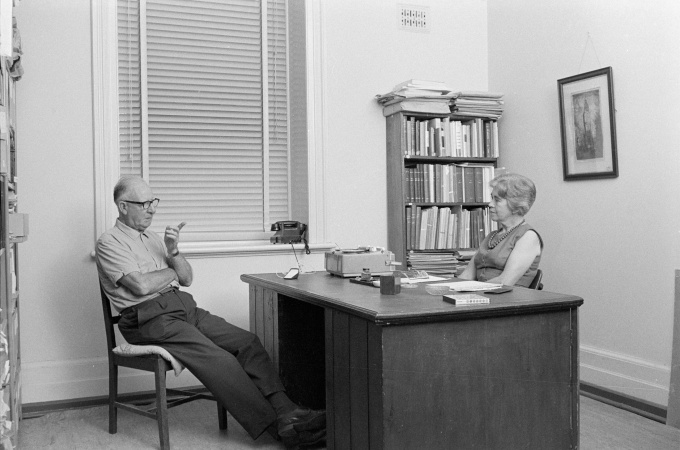

I think it said in the advertisement to call the library for details of the job. So I went in to ask for details and whoever was on the readers' desk said, "Oh I think you'd better see Dr Battye."

Dr Battye had a bit of a chat and gave me the form and whether it was because I knew his niece, Margaret Battye, who had been at the university with me, I don't know, but to my great astonishment I was offered the job.

Of course, no one had archives qualifications because such things didn't exist then, but I didn't feel I was particularly well-qualified because I didn't do history at the University.

There was an awareness of the need to preserve the State’s history. They did have a body called the State Archives Board, of which Dr Battye was the chairman.

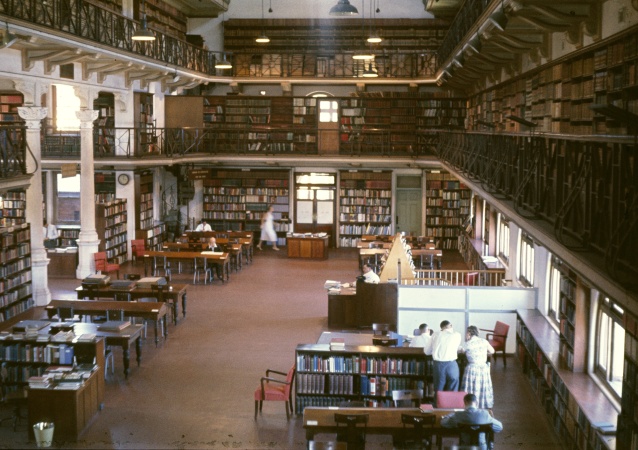

In my first years in the archives, there had been no money available during the war years. Some of the staff had been away at the war. There were only three 'professional' (I suppose you might say) librarians, who worked upstairs in the old Hackett Hall which still exists and is now used by the museum. The staff, when you think what it's like now, was incredibly small.

The portion of the building that ran through to Francis Street, the ground floor of that was the Battye residence, and there was a sort of no-man's land where a lot of material was stored in between on the ground floor. The upper floors were used as stack for the library itself.

But one of the extraordinary inconveniences, and I suppose ways of economising, was that there was only one telephone in the building. When Dr Battye went downstairs to lunch, the telephone was switched down to the house, and at times during the day when Mrs Battye wanted to make personal calls, the phone was no longer coming into the library. It went into the Battye residence, and, for people who had queries or information for the library, it was not accessible at the time.

When I was appointed, I was given a separate telephone which was a great boon I can assure you.

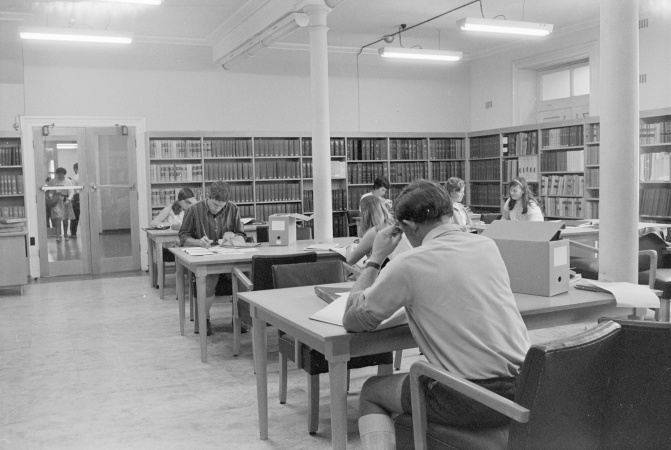

I don't think very many people outside professional people were very much aware of the archives in the library for quite a while. When I say professional people, I mean people who were engaged in some sort of historical project.

I was responsible for the transfer of records from the government, and one of the first things that I knew that was important and that I must do (as a result of my reading) was to make contact with government departments, and I concentrated on that rather than on private material because I thought it was best.

I spent quite a lot of time in the old – they call them the 'dungeons' – the old storerooms in the basement of the Treasury building. However, the archives function, although we were in the library, it functioned under the direction of the Premier's Department.

So I went to see the undersecretary of the Premier's Department and explained the position, and he wrote a suitable letter, and the problems were solved. It was a useful association with the Premier's Department. I did at that stage institute a regular circular letter to departments to say that no records were to be destroyed without reference to us, and requesting that material be transferred as soon as possible. There was quite a lot more material that came in.

The next addition to the staff occurred because I became very much aware of the necessity to preserve material that so far had been rather badly treated. There had been very little thought given to the preservation of material.

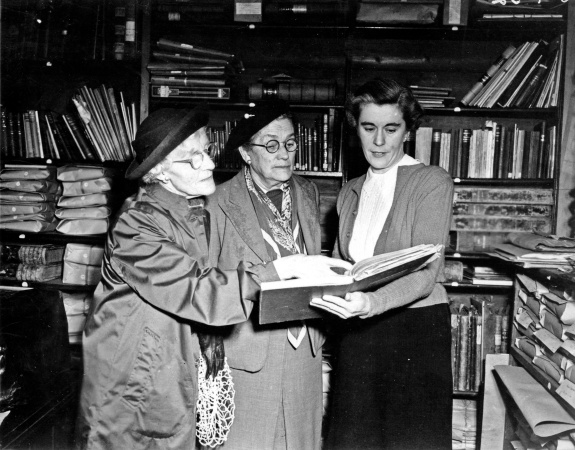

Newspapers for instance, the very first West Australian newspapers which began in 1833, were stored down in the newspaper room and they were hauled out by these old gentlemen who used to run it, and anybody could have them.

When I'd been there for a little while, I was able to wake up to the situation. There was no restriction on how they were handled. Bits were sometimes cut out over the years when people couldn't be bothered writing down what they wanted to read. There was a great deal of carelessness with regard to materials generally, and this also was true of the rare books in the stack.

A very few of the rare books were kept in a cupboard in Dr Battye's room, but there were a great many extremely valuable rare books in the stack. One of these was brought to my attention one time by Mr Charles Gardner who was the Government Botanist and whose name is very well known for his writings on botany. He came in with a copy of Lindley’s Botany which had been in the stack and which he had kept home for several years because he felt it wasn't safe. Now if I would keep it in my office he would bring it back.

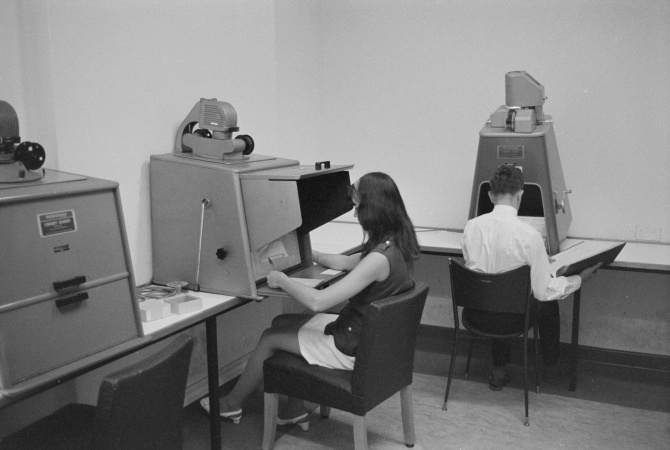

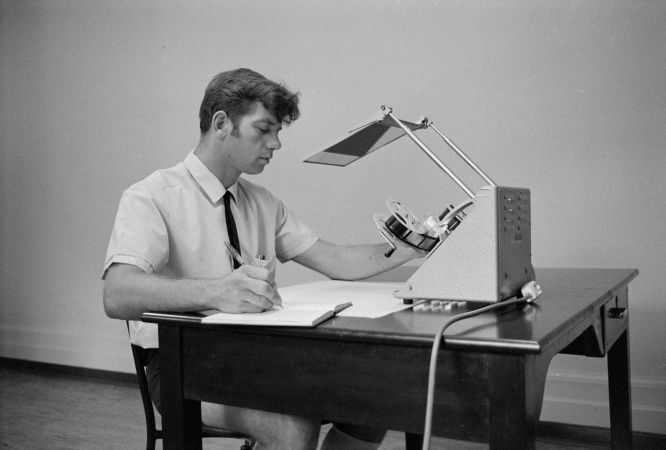

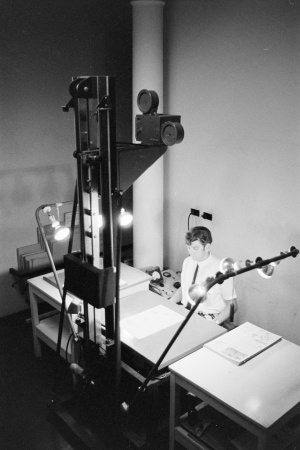

So in 1950, I started agitating, putting forward proposals to the trustees and so on, for a program to microfilm the newspapers, and to ensure that then the microfilms would be used and the originals would be preserved.

In 1956, there was a formal opening to the new Battye Library to make the public aware of the new facilities that were available.

When I retired, I was given the usual farewell parties and some very pleasant celebrations of my retirement at that time. There was quite a bit of press publicity at the time too.

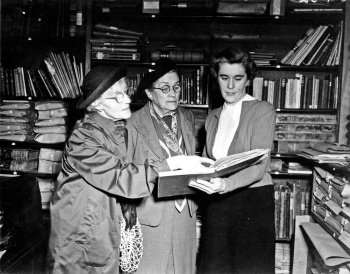

The gallery below includes photos of Mollie Lukis working as a State Archivist as well as photos of people and places mentioned in her interview.

The State Library of Western Australia regularly shares oral histories on Facebook. If you would like to view the original story about Mollie Lukis on our Facebook page, follow the links below:

Part One (published on 27 August 2024): Reading Secretly Under The Bedclothes - The Humble Beginnings Of Our First State Archivist

Part Two (published on 28 August 2024): Agitating For Change - The Achievements Of Our First State Archivist

The interview with Mollie Lukis is available online (Call number: OH2527)